The following is a reblog of a post from last week by Assistant Coordinator Kit Heyam on their own blog, Unbeseeming Words.

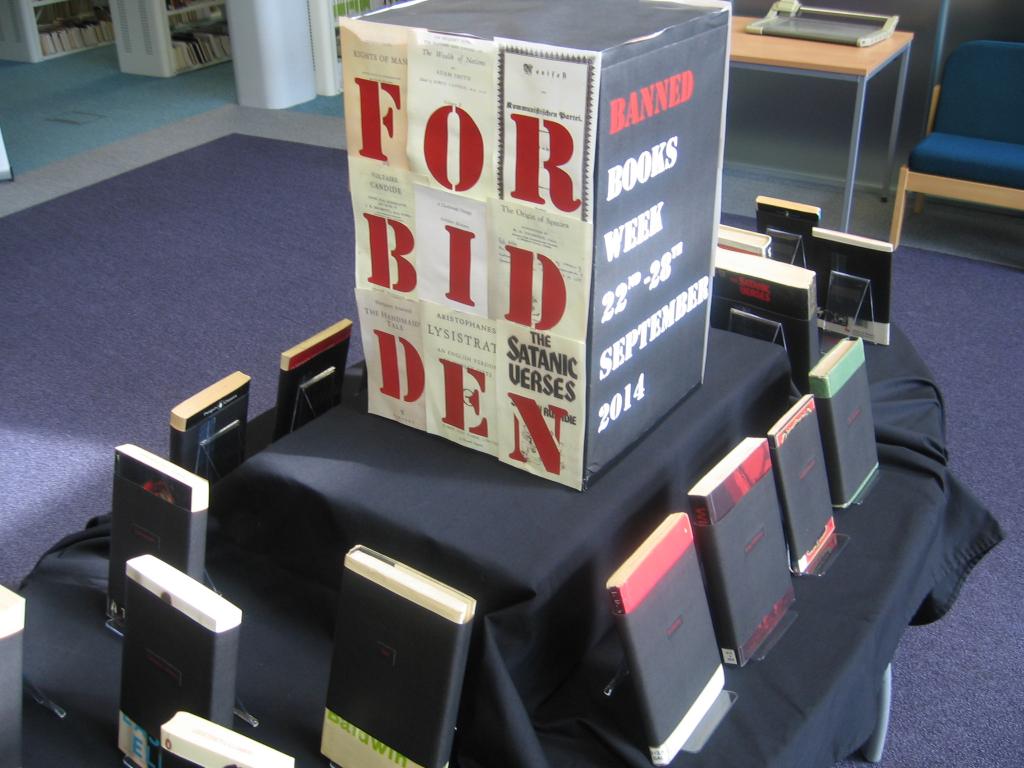

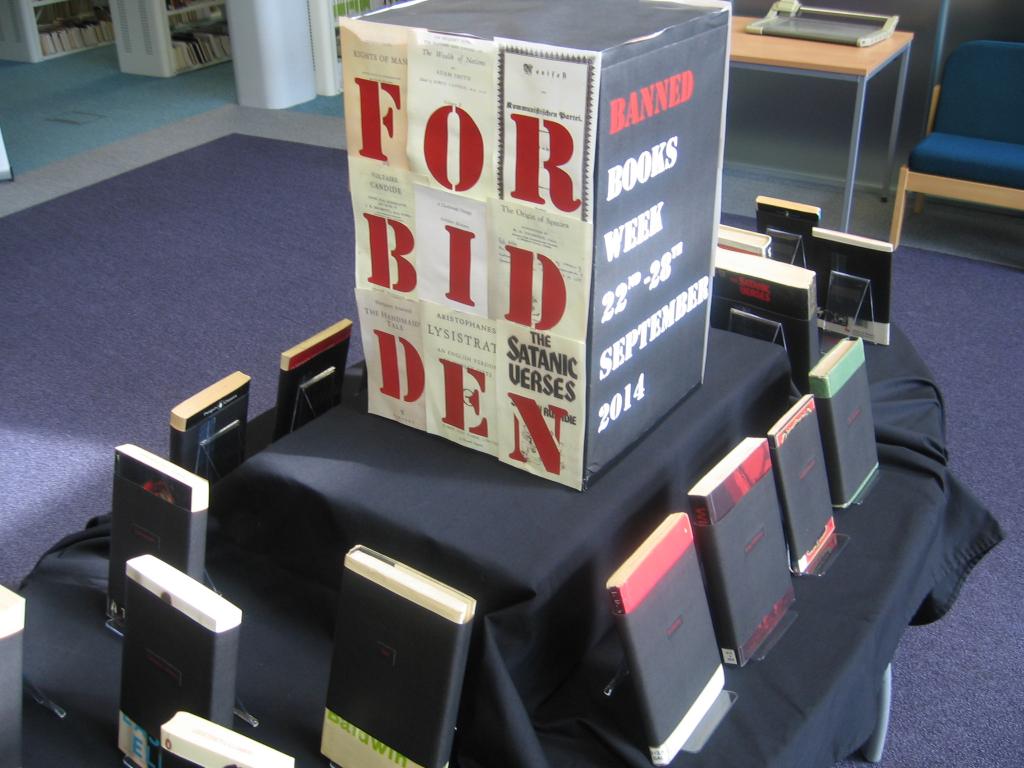

So this week, apparently, is Banned Books Week. It’s a US initiative created to “celebrate the freedom to read” – and since I work on LGBT-related stuff, which a good many people are frothing at the mouth and trying to ban right now, it got me thinking. It would be easy for this post to be about the many books which have been, and are still being, censored for LGBT+ content. This fab display in Leeds Trinity University Library, my sometime workplace, conceals each once-censored book behind a black cover with a one-word indication of its unacceptability, and there’s a copy of The Well of Loneliness emblazoned with the word “LESBIANS”!

But there’ll be someone else out there on t’internet who’s written that post already, and better than I ever could. In any case, we can all figure out (depressingly enough) why people would want to ban these texts. What I find more interesting is how certain books slip through the net – which is something that homoerotic texts in early modern England managed to do, with what some would consider to be surprising regularity.

One of my favourite early modern poets (whose work – though not the most explicit poem, sadly – I’m looking forward to teaching this semester) is Richard Barnfield. Whenever I show Barnfield’s poem The Affectionate Shepherd to friends or family, their reaction is almost invariably the same: they giggle, blush, and then ask, “How on earth did that get published?” I have to admit that, looking at the opening stanza from a modern perspective, I can see what they mean:

Scarce had the morning starre hid from the light

Heavens crimson canopie with stars bespangled,

But I began to rue th’ unhappy sight

Of that faire boy that had my hart intangled;

Cursing the time, the place, the sense, the sin;

I came, I saw, I viewd, I slipped in.

In case you were wondering: yes, that last line is innuendo. It gets better:

Then shouldst thou sucke my sweete and my faire flower,

That now is ripe and full of honey-berries;

Then would I leade thee to my pleasant bower,

Fild full of grapes, of mulberries, and cherries:

Then shouldst thou be my waspe or else my bee,

I would thy hive, and thou my honey, bee.

If the first two lines of that stanza weren’t enough, think about what wasps and bees do with their stings… It’s fantastic! And it was printed in 1594!

If this had come out (sorry) in the nineteenth century, I can’t imagine the presses would have looked at it twice – the first look would have had them reaching for the smelling salts. So why wasn’t it censored in the sixteenth? There’s been a lot of work, and a lot of arguing, about the extent and effects of early modern press censorship, but it can’t be denied that in England texts were censored far more often for political or defamatory content than for erotic. (Debora Shuger has argued, convincingly I think, that this is in part due to the way our censorship laws evolved from Roman law.) What writers like Barnfield had to watch out for, then, was not state-imposed censorship, but what Kenneth Borris has called “sodomitical reinscription”. They were presenting their work as something unobjectionable – in Barnfield’s case, as an imitation of Virgil’s second eclogue* – and needed to avoid it being interpreted as sodomitical (in the early modern sense, something socially and/or sexually disruptive). In other words, they weren’t so much in danger of being censored, but censured.

How, then, did Barnfield evade such censure? The answer, I think, lies in a strategy that Annabel Patterson has identified as characterising early modern censorship-avoidance more generally: a kind of contract of tactical ambiguity, by which writers made it possible for their work to be construed as unobjectionable, and censors would interpret it that way if at all possible. This is particularly applicable to homoerotic texts because of the widespread reluctance, in early modern England, to recognise that sexual relationships between men ever existed: the few cases that reached the courts had additional circumstances – political transgression, differences of age or social class – that compelled the sexual transgression to be recognised and dealt with. So when readers picked up Barnfield’s book, they had a choice of interpreting it as good ol’ humanist classical imitation, or icky damnation-worthy mansex. If the latter occurred to them, they’d be worried: “Should I tell someone? But they might think it says something about me that I thought of it! And it’s the “vice amongst Christians not to be named”, and I’d be talking about it… You know what, it’s probably nothing.” Better to assume everything’s fine than to wrestle with social, discursive and religious prohibition to confront other possibilities.

And so Barnfield ended up a published poet, and a perversely inappropriate subject for Banned Books Week (although I suspect that’s mainly because his verse remains undeservedly obscure outside of universities – possibly I’ve just initiated a series of homophobic book-burnings…) But it wasn’t an entirely happy ending. In 1598, three years after the publication of the second edition of The Affectionate Shepherd – an edition prefaced by a disclaimer by Barnfield: “IT’S JUST CLASSICAL IMITATION HONEST!” – his family drew up documents which disinherited him in favour of his younger brother Robert. They remained unconfirmed until April 1602, just after Robert’s marriage. Hence they could be seen as a threat based on Richard’s own failure to marry and reproduce – a threat enacted when, contrary to social expectations, the younger son married before the elder. Richard died a disinherited bachelor. It’s a timely reminder that, despite strategies of ambiguity, there was no perfect world of textual and sexual tolerance in early modern England, and that daring literary content is rarely entirely without risk – as too many writers across the world still find today.

* which, not incidentally, is WELL HOMOEROTIC in its own right, but classical imitation was such a Renaissance convention that claiming to be imitating Virgil was one of the safest ways to include love or sex between men in your writing. I’d love to tell you more about it, but that would be my masters thesis, and it’s a bit long for a footnote…

Latest posts by Ynda Jas (see all)

- Call for events for 2020! - 17 September 2019

- Call for events for 2019! - 13 October 2018

- Call for events for 2018! - 3 August 2017

I agree but the main censorship in the modern media is the cinema particular the bio pic. people are still unaware of the extraordinary gay people who have sculptured the modern world and to be honest the ancient one as well (to be flippent for a minute the sistine chapel would be magnolia white if it was not for gay people ) thanks to Charlton Heston

Indeed. That’s what we’re trying to change!

I know you are! a very worthwhile project

RT @yorklgbthistory: ‘No Barnfield in Banned Books Week: avoiding censorship in early modern England’: http://t.co/sXRP8hmB1J